|

330 GT Registry |

|

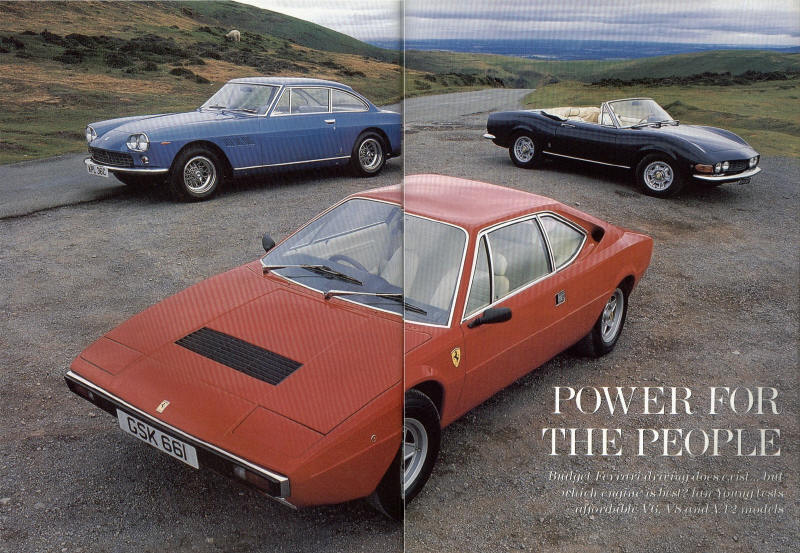

A front-engined open sports car, a mid-engined 2+2 supercar, a front-engined family car: was there ever a more disparate group of motor cars brought together for a single road test? Probably not. But forget for a moment that comparison tests are often as highly contrived as clearly formulated; and pray overlook that the protagonists may convene atop remote Welsh mountains in order to discover which is best-suited to its chosen demographic group.

Focus, instead, on a

road test where the sole purpose is to find the best hunk of authentic Maranello

muscle for as little cash as possible. Cheap Ferrari power is the objective;

Fiat Dino Spyder (2-litre V6), Ferrari 308GT4 (3-litre V8) and Ferrari 330GT

(4-litre Vl2) are the objects. A crude comparison? Possibly. Fun? Definitely.

FIAT DINO SPYDER

The immortal Dino 206GT and 246GT cars of 1968 and 1969 were the first and only recipients of Ferrari’s light, compact V6 engine — right? Wrong. The Fiat Dino Spyder — designed (as was the 206/246 series) by the mainstay of Maranello styling, Pininfarina — predates the 206GT with a Dino engine by almost two years. But don’t be alarmed. There was no subterfuge here; no furtive passing of blueprints in dusty Milanese parking lots. The decision to put Vittorio Janos light-alloy V6 in a Fiat bodyshell was made jointly by Fiat supremo Giovanni Agnelli and Il Commendatore himself.

It was a simple trade-off: Ferrari needed to see 500 of its V6 motors in a production car pronto in order to homologate the design in time for the 1967 Formula 2 championship. Fiat, on the other hand, was looking decidedly under-endowed in the desirable sports car department and would clearly benefit from the charisma boost an association with Ferrari would give.

It was a successful partnership — up to a point. Unfortunately for Fiat, the entire operation needed to be completed in 18 months from handshake to homologation. For a company that was already flat-out on the new 124 range of budget sports cars, the design and manufacture of yet another brand-new car was a tall order. For outside assistance Agnelli entrusted both the styling and the manufacture to Pininfarina. The Dino engines came straight from Maranello, were slightly detuned by Fiat’s Alfredo Lampredi and — unlike those in Ferrari’s own midships-motored 206 and 246 models — were installed in the traditional position at the front. Debuted at the 1966 Turin Show (preceding a Bertone coupé version that was shown at Geneva one year later), the Spyder turned out a surprise hit. Setting aside the sweet-sounding engine, the specification didn’t look terrifically promising on paper. A conventional live axle with leaf-spring suspension at the rear and an all-synchromesh five-speed gearbox, a In Fiat 124 Sport, left some commentators reaching for their red pens before the new model had even turned a wheel.

Then came the surprise: the Spyder had performance that lived up to its stunning shape. Eminent Motor journalist Charles Bulmer wrote at the time that ‘if you didn’t know that the Dino had a live axle at the rear you would think it had very good independent suspension all round.’ Fiat technicians credited much of the car’s success to the then-new Michelin XAS tyres, which gave excellent directional stability at high speed — the Dino was capable of almost 130mph — as well as a good level of grip during energetic cornering.

We drove both the 2-litre and the later 2.4-litre (with independent rear suspension) versions of the Dino Spyder last year, and came away highly impressed by its surefootedness and extraordinary stability under cornering at very high speeds. Our test car on this most recent occasion was patently in need of some new suspension bushes, suffering a slackness of response that is not typical of the model. It remains the most forgiving and, in that respect, practical of our test trio.

At the wheel the average-sized driver would probably want a little more room to manoeuvre. The footwell is narrow and access is hindered by a large wood-rimmed, chromed-triple-spoked Nardi steering wheel. There are rear seats but, with adults up front, their usefulness would probably be limited to the carriage of small bags only. The overall impression is positive, though. Comfortable leather-trimmed seats, a well-designed facia and an inspirational forward perspective are the classic ingredients from which to derive maximum sporting satisfaction in the true Latin tradition.

Clearly there is little that can touch Maranello’s-own Dino 206/246 for a combination of grace and aggression — but a good Dino 246GTS can cost £40,000 these days. Compare that to the cost of a pristine Fiat Dino Spyder: £15,000; even less for Bertone’s equally good-looking coupé. That makes good sense for those seeking affordable cavallino urge. Should one be bothered that it doesn’t carry the coveted badge? I don’t think so. After all, it looks like a Ferrari and, by God, it sounds like one.

|

Living with V6 Power: the Fiat Dino 2-litre |

|

|

BRIAN BOXALL owns no less than three bright red Fiat Dino Spyders now and has owned as many as ten over the years. The model pictured here is a 1970 2.4-litre example. “I bought it just over one year ago he says. “There were a few blemishes on it, a damaged door and a problematic cylinder head. I had the bodywork done by a local man and the engine overhauled by Mike Elliot at Superformance. “I’m known as a bit of a nutter among Dino Spyder enthusiasts — I drive the cars a lot and never have the hood up. During an average year I will probably clock up several thousand miles in them, and that is just driving at weekends. “I’m not an ace mechanic, so usually farm out major maintenance work to specialists. Much of the work could be done at home in the garage but I would recommend leaving the engine to the experts. “One of the problems with the Dino Spyder is that you are at the mercy of the few companies who sell spare parts, and bits such as hood frames and windscreen frames are almost impossible to source because nobody makes them, Parts that are common to both the Spyder and the Dino Coupé are less of a problem. “I do hanker after owning a real Dino 246 or 206, and maybe if I clear a couple of my Spyders I will be able to afford one, but I would always want to own at least one Fiat Dino Spyder". |

|

| Engine: 65°V6 Displacement: 1,987cc Bore & stroke: 86 x 57mm Valve gear: DOHC Compression: 9:1 Carburetion: 40DCF x3 Lubrication: wet sump BHP: 180 @ 8,000rpm |

Front suspension:

wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers Rear suspension: live axle, semi- elliptic springs, telescopic dampers Value today: (con A) £14,000 Specialist: Phil Stafford, Rosneath Engineering, Hartfield, East Sussex. Tel 01892 770032 |

DINO 308GT4

It is ironic that the Ferrari Dino 308GT4 we have on test here should happen to be wearing so many prancing horse emblems across its skin. Strictly speaking, there shouldn’t be any there at all. When the 308GT4 was introduced to the world at the Paris Salon in October 1973 it boasted just one ‘Dino’ badge on the nose and the solitary inscription ‘Dino 308GT4’ on the boot lid. That hints strongly at the mood with which Bertone’s 246 successor was received. Not only was the angular design seen by some as ill-conceived and ill-befitting the romantic Ferrari tradition but, also, the new car was not even badged properly. It was almost as if Maranello wanted to distance itself from its latest progeny.

Two years later (after our test car was built) Ferrari began to bestow the GT4 with bona fide badging and the maligned 2÷2 was imbued with a measure of respectability. Unfortunately, it was a case of too little, too late. Bertone’s contract with Maranello was never renewed and Pininfarina’s conspicuously classical 308 GTB — also with a V8 engine amidships — stormed on to the world stage, utterly ruining the GT4’s credibility as a thoroughbred Ferrari. The GT4 limped on until 1980, when it was axed after 2,826 examples had been made.

A melancholy tale, then... melancholy, that is, for the 308GT4 but not for a present-day Ferrari enthusiast on a limited budget. Two reasons why this is SO: first, the GT4 is the bargain Ferrari. As recently as five years ago you could buy a runner for under £10,000, though values have since risen to between 15 and 18 grand — largely thanks to magazines such as this one banging on about what an unrivalled budget supercar the GT4 is. The second reason is simple: it really is a very good car.

Frankly, it was doomed from the moment Pininfarina put the finishing touches to its immediate predecessor, the immortal ‘baby Ferrari’ Dino 246GT. Bertone’s brief was to design a car that was as compact as the 246GT but with a 2+2 layout and a brand-new V8 engine squeezed in behind; a task that was hardly the envy of designers the world over. That it has been enjoying a steady renaissance over the last ten years is entirely to the Turinese designer’s credit. The stub nose, high waistline and angular roofline are all design cues with which Ferraristi have grown more sympathetic. People talk about innovation now, not embarrassment.

There was never much of a problem with the car on the road. Indeed on a pound-for-power basis you will be hard-pushed to find a more nimble, exciting and sure-footed mid-engined missile from that era. At the heart of the GT4 is Ferrari’s first ever roadgoing V8 engine, the lineage of which can be traced back to the V8 F I engine designed by Angelo Bellei for John Surtees’ World Championship-winning car of 1964. The 3-litre GT4 unit had four overhead camshafts, four twin-choke Weber 40DCNF carburettors and a brace of Marelli distributors, and produced 255bhp at 7,700rpm. A top speed of approximately 148 mph put it in healthy competition with ‘baby supercar’ rivals, specifically the Maserati Merak and Lamborghini Urraco.

Of our three test cars, it was the 308GT4 that provoked most roadside comment. It has far and away the most aggressive poise, and that purposefulness carries through to the cabin, where the V8 whistles and whines asthmatically yet fiercely behind you. It is an intrusive presence unique to this breed of Ferrari road cars, one that reflects the mood of a time when power-obsessed manufacturers were squirming in the wake of the oil crisis. Frenetic urgency and controlled release of energy are characteristics of the mid-mounted V8, compared to the happy-go-lucky V6 and the imperious V12.

The 308GT4 is probably closer to the popular notion of how a Ferrari should be than either the Dino-engined Fiat or the 330GT. The super-heavy clutch with super- long travel, the traditional slotted chrome plate at the root of a stark, chrome-plated gearlever, the polished aluminium dash panel housing the full complement of functional-looking Veglia dials and switches: the overall impression is both seductive and intimidating, a bit like a catwalk queen with Mensa brainpower.

Constantly frustrated on the blind mountain lanes and suffering aural monotony on the motorways, I found solace on fast but meandering roads that were some where between the two. It was here that I was able to avoid bogging the carburettors down at low revs and subjecting the suspension to an overdose of road- surface abuse. Pin-sharp steering, confident brakes and neutral handling endow the 308GT4 with all the classic traits of a well-balanced mid-engined sports car.

All of which make it an excellent choice as a budget supercar. However, unlike the Fiat Dino and even (more in a moment) the 330GT, it doesn’t sit easily with the picture of daily runner. Limited visibility, shortage of storage space and maximum conspicuousness make journeys to the supermarket questionable ventures. Nevertheless it sit securely on its pedestal as the most economical pure-breed Ferrari to run. If you start with a good, rust-free car with a well-documented history — such as our test car from north London specialists Hendon Way Motors — then you could find yourself spending as little as £500 a year on running costs. But don’t hold me to that. Any Ferrari is still a highly temperamental hunk of Latin engineering.

|

Living with V8 Power: the Dino 308GT4 |

|

|

SIMON OXENHAM: “It seemed in driveable condition, apart from the fact that the calliper pistons were seized and the brakes locked solid. On closer inspection, I discovered that the brakes, running gear and suspension all required a complete overhaul. The work took several months but it was more time-consuming than costly, since the majority of parts were serviceable. “I was also unhappy with the respray and arranged for the body to be painted again. This work took about five weeks, during which time the upholstery was sent away for minor repair work and treatment, the wheels were repaired and some new tyres were fitted. “The car had covered just 56,000 miles and it was sold with a full service history, so the engine was in a near-perfect state of health. “In three years

of ownership I have since covered several thousand miles “Overall, I reckon the Dino is tremendous fun, very exhilarating to drive and relatively easy to maintain — but you need to watch the budget." |

|

| Engine: 90° V8 Displacement: 2,926cc Bore & stroke: 81mm x 71mm Valve gear: DOHC Compression: 8.8:1 Carburetion: 40DCNF x4 Lubrication: wet sump BHP: 250 @ 7,700rpm |

Front suspension:

wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers Rear suspension: wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers Value today: (cond A) £18,000 Specialist: DK Engineering,Unit D, 200 Rickmansworth Rd, Watford WD1 7JS. Tel 01923 255246 |

FERRARI 330GT

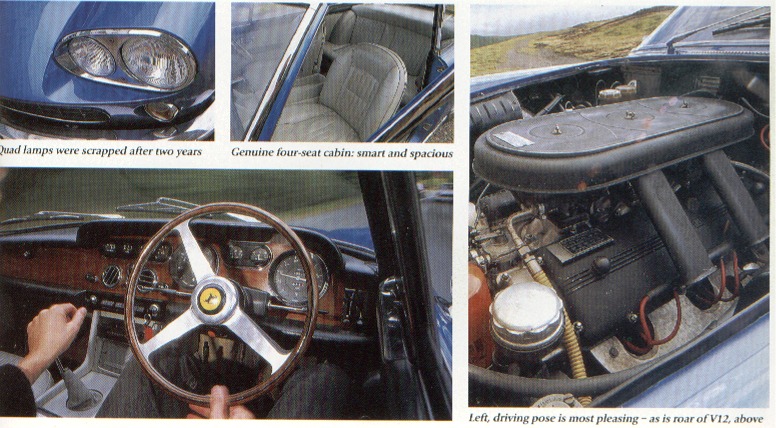

When the Ferrari 330GT 2+2 was launched at the Brussels Show in January 1964, it was widely considered the most refined model ever to have left the Maranello production line. Battista Pininfarina’s striking genuine four-seater came in direct succession to the marginal family facilities offered in the 250GTE three years earlier. Back then, Ferrari was in need of a bigger car yet one that retained the thoroughbred instincts of a gran turismo cavallino. By shifting the engine a few inches forward, it had been found possible to create a virtual 2+2 without lengthening the wheelbase from that of the then-current two-seater models. Even so, one would have hesitated before calling the 250GTE a ‘family Ferrari’.

Main

pic, 330GT was seen as something of an ugly duckling at first. Now it’s

recognised as first genuine Ferrari for the family

The 330GT was a different matter. There were two inches extra on the wheelbase and more legroom in the back. There was more headroom, too. But perhaps the most telling development was the installation of an all-new 4-litre V12, breathing through three twin-choke Weber carbs, that was based on the similar-capacity 400 Superamerica engine. This significantly outperformed the powerplant of the outgoing 250GTE and enabled the model to find itself a comfortable niche in the prestige car market as a genuinely spacious, luxurious sporting machine. Ferrari needed a mass-production car that would draw more pragmatic clients, and both 250GTE and 330GT delivered in this respect. More than 2,000 examples of the two models were sold between 1960 and 1967, when the 330 was replaced by the 365GT 2+2.

As one might expect from the world’s most celebrated builder of motor cars, the 330’s twin blessings of luxury and sporting prowess are still highly effective 30 years later— a remarkable achievement. Of our three test cars, the self-effacing Vl2 was by far the most suited to a journey that combined a long haul up the M40 with several hours’ weaving through unnervingly narrow Shropshire lanes. Were it not for a persistent cooling problem, probably due to a faulty thermostat, I suspect that we would have come away even more in awe of this most misunderstood of Maranello’s brood.

Misunderstood? Well, yes. Less than enthusiastic murmurings have dogged the 330 throughout its life. People talk about the twin headlights at each front corner, the soft body lines, the bulbous boot, and they wonder whether Pininfarina sacrificed the razor-sharp styling of the 250 in his search for a truly functional Ferrari. By popular request, the twin headlights were deleted within two years. A shame, that, I’d say.

The

jury may still be out when it comes to the styling but when you start talking

about behind-the-wheel behaviour, the verdict is pretty much unanimous. The

330GT is a superb driver’s car. Taking it, again, in the context of our test

trio, it provides what is assuredly the most satisfying all-round driving

experience. From the second when you drop on to those ageing leather seats —

grown well-worn and creased over the years — and begin the oddly fulfilling

turn-key-and-push starting procedure, you are left in no doubt of the noble

lineage of the equipment at your disposal. And there is a moment—when all 12

cylinders rumble into life, when the heavy steel door swings shut and you are

left alone with your thoughts — that, just for an instant, you imagine yourself

selling all your worldly goods and living in a Ferrari for the rest of your

life. It’s that good.

The

jury may still be out when it comes to the styling but when you start talking

about behind-the-wheel behaviour, the verdict is pretty much unanimous. The

330GT is a superb driver’s car. Taking it, again, in the context of our test

trio, it provides what is assuredly the most satisfying all-round driving

experience. From the second when you drop on to those ageing leather seats —

grown well-worn and creased over the years — and begin the oddly fulfilling

turn-key-and-push starting procedure, you are left in no doubt of the noble

lineage of the equipment at your disposal. And there is a moment—when all 12

cylinders rumble into life, when the heavy steel door swings shut and you are

left alone with your thoughts — that, just for an instant, you imagine yourself

selling all your worldly goods and living in a Ferrari for the rest of your

life. It’s that good.

Off the mark the clutch and steering seem heavy but it doesn’t last. A sensible, upright driving position and very large three-spoke steering wheel afford plenty of leverage and control. The gearbox is a four-speeder, with synchromesh on every gear and an overdrive that kicks into action the very millisecond you flick the stalk on the right-hand side of the steering column. This is an excellent box, too — very precise and quick to change. It sets the scene for the whole drive, because the ratios are those you would expect to find in a lighter, lower and significantly more blatantly attitudinal sports car.

|

|

“Could you hand me that torque wrench ?“ Someone looks a little sheepish... 330GT was temperamental |

A few telltale

figures an output of 300bhp when the engine is spinning at 6,600rpm; 0-60mph in

7. I seconds, 0-100mph in a whisker over 15 seconds. These were mightily

impressive figures compared to those of its 250 predecessor, thoroughly

vindicating eminent Sixties journalist John Bolster famous comment that ‘there

is no better car than the car of tomorrow’.

Of our three protagonists, it clearly remains the most practical from the point

of view of daily driving. Superb outward visibility; an elegant and functional

cockpit layout; power-assisted disc brakes that seem immune to fade: all these

are mandatory attributes in the modern motoring world, and the mid-Sixties 330

falls short on none of them.

Whether or not it is possible to run such a car on a budget is a different matter. Certainly the 330 is the most expensive of our trio to own today. Values for a good example range from £25,000 to £30,000. Surrey-based specialist Talacrest is asking £30,000 for our test car which, with the cooling gremlin traced, can be considered a fair price for a fine example with an interesting history and on-the-button dependability.

The cost-cutting V12 Ferrari owner faces a difficult predicament: she/he owns a machine that needs to be driven, and driven for decent lengths of time in order for it to be operating at optimum levels. Yet, as with any car, high mileage increases the risk of problems occurring. So is the 330GT a good-value V12 Ferrari? Certainly — even when compared to less sought-after models such as the 250GTE, 330GTC and 365GTC/4 but it’s vital not to daydream that you are buying into anything less than some of the finest motoring that money can buy. It’s an expensive investment.

|

Living with V12 Power: the 330 GT 2+2 |

|

|

“The 330GT (1965, series 1 model) has been in my family since 1966, when my father bought it. I took it over from him about eight years ago. No work of any real consequence had been done on before then; it had spent most of its life running in partnership with an Aston Martin DB4 GT and taking part in several rallies in Holland, Belgium, Italy and the United Kingdom. Also, three or four times a year it would be used on driving holidays through France. “Nowadays I use it principally for club meetings and gatherings and generally reserve it for use in the summer months. I don’t mind getting it wet but the winter salt can cause dreadful problems to the bodywork. I only live between ten and 15 miles from work, which is not enough of a journey to make daily commuting in the 330 worthwhile. These cars, particularly the big V12s, need to be driven for a good amount of time if they are to be driven properly. “I do most minor maintenance work myself. My father was an engineer and he passed on what he knew about the car to me. It’s really not that difficult to maintain if you stick to the simple things. I’ve had the head off, and worked on the gearbox and the clutch, It’s only when problems occur in areas like the differential and the engine that you need to call in professional help. “I go to Mortimer, Howton & Turner for parts, the availability of which is much better than for, say, a Maserati." |

|

| Engine: 60° Colombo V12 Displacement: 3,967cc Bore & stroke: 77mm x 71mm Valve gear: SOHC Compression: 8.8:1 Carburetion: 40DCZ6 x3 Lubrication: wet sump BHP: 300 @ 6,600rpm |

Front suspension:

wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers Rear suspension: live axle, semi- elliptic springs, telescopic dampers Value today: (cond A) £33,000 Specialist: Cohn Clarke, 247 Acton Lane, Park Royal, London NW1 0 7NR. Tel 0181-961 9392 |

VERDICT

There is no such thing as cheap Maranello power when the red mist drops, revs tip 9,000 and pistons punch through that elegantly-sculpted bonnet. If gremlins get to any of these engines, call your bank manager before you do anything else. But the outlook is not all gloomy: preventive maintenance and regular use can ensure good reliability from all of these cars.

Pick a winner from the three? To be honest, I’m torn. My heart goes for the blue-blooded 330GT 2+2; my libido for the red-hot Dino 308GT4. My head? The Fiat Dino Spyder. Am I playing it too safe?

Hilltop hiatus: now which car to choose?

Fiat Dino Spyder is primitive fun;

Dino 308GT4 is aggress and agile;

330 is Vl2 Ferrari at noble heart — but costly

THOROUGHBRED & CLASSIC CARS OCTOBER 1996

© EMAP National Publications Ltd. 1996

DOUGLAS

CROWTHER:

DOUGLAS

CROWTHER: