| 330 GT Registry |  |

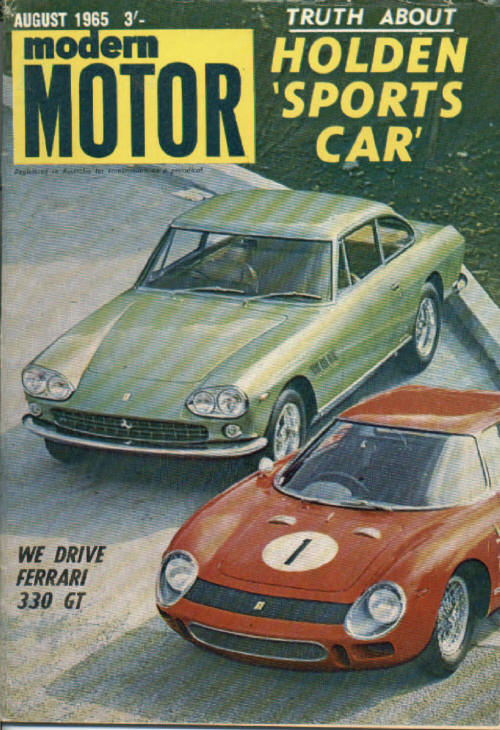

MODERN MOTOR—August 1965

Lines are smoothly aero dynamic, with lots of glass. An odd touch is the “hungry guppy” profile of headlights and intake.

|

| Rear screen is huge, tail unusually rounded for a Pininfarina creation. Big quick-pour filler for thirsty 20 gallon tank. |

In the past Ferraris have been magnificent cars for performance and safety—but if you looked closely you could find faults with the bodywork that made a buyer raise his eyebrows at the £8000 tag.

Accommodation was strictly limited, too, and, while the beautiful “two-plus-two” was roomier than any other comparable GT car, it was really only a makeshift.

Then last year came the 330 GT — and it was immediately accepted by the lucky few who could pay for the most exciting name in the motoring world and yet wanted room, either for their family or so that their friends could enjoy the ultimate in Grand Touring motoring.

Let me tell you how Enzo Ferrari himself sees his most popular model — condensing slightly from his factory’s publicity material:

“The bodywork is by Pininfarina and the Maestro has created another masterpiece. The modern lines emphasize the essential characteristics of elegance: purity and simplicity. The sides, of classic design, blend with the roof and with the rear to offer a large boor. The curved screen has not only been studied for optimum aero dynamics but also to offer outstanding visibility.

“The front grille perpetuates the traditional Ferrari design and the bonnet has a sweeping profile as a result of studies for high-speed streamlining and good appearance. The large interior compartment has two reclining and adjustable front chairs and greater rear-seat space.

“On the dashboard, trimmed with anti-glare leather, the complete set of instruments and controls are placed rationally for easy reading and convenient finger-tip control. And there in separate individually-controlled heating and ventilation for passenger and driver.

“The four-litre 12-cylinder engine with single overhead camshafts retains the qualities of robustness and smoothness that made it famous: it is powerful. docile, obedient and has a flexibility of speed range unequalled in any ether Grand Touring car.”

Under the Bonnet

The V-l2, 60-degree engine has a bore of 77mm. and a stroke of 71mm. Compression ratio is 8.8:1 and maximum power is 300 b.h.p. at 6600 r.p.m. The crankcase and cylinder block are cast in Silumin with shrunk- in liners. The fully machined crank shaft has seven bearings, the conrod coupled in pairs and running on thin-wall Vandervell bearings. Hemispherical heads have inclined overhead valves operated by roller rockers and single camshafts.

Tappet adjustment is by hardened screws and the camshafts are driven by silent chains with turnbuckle adjustment. Pressure lubrication is by gear-driven oil pump. Ignition is by twin Marelli coils and distributors with automatic advance. Fuel is fed by a mechanical pump with an additional manually-controlled self- regulating electric pump. Carburetion is by three twin-choke Webers and cooling by radiator and a thermostatically controlled Peugeot patent fan.

Clutch is a single dry plate with cushion centre. The four-speed all synchromesh gearbox has a remote-control lever, fourth speed is direct plus a self-cancelling electric overdrive. The speeds attainable in gears are 50, 75, 100, 125 and 152.

Independent front suspension uses wishbones, helical springs, roll bar and telescopic shock absorbers. The back has semi-elliptic leaf springs and hydraulic shock absorbers, supplemented by helical springs. The rear axle is rigid with fore and aft locating rods. The steel tubular frame is extremely stiff. Left- and right-hand steering to choice.

Disc brakes are on all four wheels, operated by a tandem master cylinder. with separate circuits and two servo boosters. Hand brake is floor-mounted.

Wheelbase is 104.2in., front track 55in., rear track 54.5in. Weight is 3040 Fuel capacity is 20 gallons, consumption is 14/16 mpg. and wire wheels with light alloy 6 rim take Pirelli Cinturatos (H.S.) size 205 by 15. Four headlights match the car’s high-speed potential.

And there you have it — the new 330 GT embodying all the advanced characteristics of the true GT car;

its innovations added to the traditional Ferrari values combine to make the luxurious and powerful car the logical product of 20 years’ experience.

| |

| ABOVE: From front you’d hardly know it was the same car — four eyes, wide grinning grille with Ferrari’s Prancing Horse in centre. RIGHT: Big 4-litre V12 fills engine bay to capacity, is topped by one-piece housing for triple carbs’ air-cleaner. She develops 300 b.h.p. |  |

Homeground Test

I was lucky enough to be able to accompany Ferrari testers giving the 330 GTs and 275 GTBs exhaustive trials at the factory last year. Michael Parker, Ferrari’s “white-haired” engineer was carrying out temperature tests on a 330 GT back from England and I went along for the ride. The countryside around Maranello is often blanketed with fog in November and to escape this we tore up into the hills and burst through into glorious sunshine.

Here Parker used the 300 horses to the full, and I was staggered not only at Parker’s skill but at the big car’s versatility. It seemed impossible that this car, which is aimed at the luxury four-seat touring market, could behave with all the savagery of a two-seat Berlinetta. But Parker had peak revs in first and second through out the mountain climb, with dabs of third up to 90, sliding with power through the corners and over the cobbles.

Even after miles of this treatment the engine was quite unruffled, all the gauges confirming this. Then we repeated the same thing using top end overdrive — such is the flexibility of the big smooth V-12 four-litre engine, which showed no irritation at being so unimaginatively driven.

After this we came down on to the plains and Parker showed me that fourth gear could be used for starting and then straight on up to 125. Automatic transmission seems hardly necessary with this sort of car!

The counter is red-lined at 6600 r.p.m., but Parker had 7000-7200 showing frequently. The big engine was smooth enough at these revs, but not as silky as the 3.3 engines used in the Berlinettas, which spin to 8000 with utter reliability.

| |

TROUBLES should be rare, but generous Ferrari tool-kit can deal with almost any crisis. Boot is wide, shallow. | BACK-SEATERS are as well served as front occupants with contoured seats; leg-room is adequate. |

Aussiť Tryout

After this heady introduction to the 330 GT in its native state, I was delighted when I recently had the chance to deliver a new 330 GT from the concessionaire in Melbourne to Scuderia Veloce Motors in Sydney.

With me as passenger was Tony Oxley, jun., whose father had been good enough to lend me his 250 coupe some years ago to run at Longford and Bathurst (Modern Motor, July 1961).

I had forgotten how imposing a 330 GT looked and I fell in love with the car as it stood awaiting us glistening in the morning sun. I had a brief refresher cockpit drill, checked around the car, oil; water, battery, tyres and hub caps, filled the tank and we purred past the Bourke Street P.O. at 30 minutes after noon.

I was home at Wahroonga by 11 p.m., wishing the trip had been on up to Brisbane, for although I’d been up since 5 am. and flown down to Melbourne that morning, I could have driven all night.

There is nothing quite like this Ferrari. I limited the revs to 4000 r.p.m., getting about 100 mph., for — although the car would have been fully tested at Maranello — a new owner might have been justifiably testy had he seen it pass him at 150!

|

| THICK, rolled edges on reclining front seats give good lateral support. Complete set of instruments (what else?) in that big binnacle. |

Once out of Melbourne, the big car strode along at an easy gait. Vision was wonderful ahead, the bonnet being visible with its forward slope, but rearward was a little restricted, due to the roof-line sweeping down. The electrically-operated windows were tightly closed, and we had a pleasant circulation of fresh air through the movable ducts on the dash. The engine was inaudible, and only a poorly-fitting door-seal emitting a whistle broke the silence.

I cruised in overdrive, which gave about 24 m.p.h. per 1000 revs, and this had all the acceleration most motorists enjoy in the indirect gears of family cars. The overdrive could be engaged and disengaged without any awareness by young Oxley, who was enthralled with the many improvements in the 330 GT over the older 250 GT. The overdrive is self-cancelling, so you needn’t remember to flick out of overdrive when changing down into third. On changing up, you go automatically into direct top.

Euroa came up in under 90min. from the G.P.O. and six gallons filled the tank. After a leisurely lunch of rainbow trout — suitable fare for Ferrari travellers, even though the trout were the Japanese deep-frozen variety — we rolled on to Gundagai, averaging 16 mpg. Albury to Gundagai took under 90 minutes and at no time did the tacho go over 4000. The speedo appeared to be about 2.5 percent fast around the 100 mark.

The driving position suited me perfectly — I am about average Italian size — but a six-footer would have to get the seat slides moved, with some loss of rear-seat knee-room. As I had the seat, rear passengers had fair room, but top hats were out.

Instrument layout was perfect; the only dial not immediately under my eyes was the clock, which was obscured by my left hand when on the wheel at 10 o’clock. How typically Italian to think to place the least essential dial so. In some cars I can think of, it would have been the oil pressure gauge!

We were using 31/34 In the big fat Pirellis, higher pressures being advised only for sustained high speed driving, such as autostrada running at 120-plus. The coupe felt very solid and utterly untroubled by the rough roads around Tarcutta. The car likes to run dead straight, and even strong cross winds have little effect. Big sweeping bends are taken without any slowing down—just a little more pressure on the big accelerator pedal, and the car follows the chosen line obediently. The handling characteristics are pleasantly neutral for cruising speeds around 100.

The huge discs, with the double servo system, are tremendously effective. Seeing a semi pull out of a parking bay just ahead, I applied the stoppers, which slowed us so smartly I could have got back on the loud pedal before coming up to the truck.

The ride is extremely comfortable, the seats giving wonderful lateral support, with heavy rolled edges holding one’s body. Lack of fatigue is remarkable and seldom associated with such speeds. I consider it due to the silent, powerful travel, the feeling of complete control and the absence of gear-changing. It seemed odd to approach Albury after miles of high-speed running in overdrive and then potter through the border town at 30, still in overdrive.

The steering, by the same wheel as I have on the LM, is lower-geared than earlier Ferraris, making it lighter around town, yet still as comfortingly accurate at speed.

The night section of the journey brought my only criticism of this fine car. As with all Italian cars, there is a warning light when the driving lights are on. This is a fairly strong small green light, which not only reflects onto the screen — to one side admittedly—but peeps behind the right-hand alloy spoke of the steering wheel, so that on a winding road, now you see it — and now, you don’t.

This is a little disturbing until you get used to it; if the car was mine I’d have it wired in on the rheostat control for the panel lights, The driving lights are well able to cope with the car’s potential, and that’s rare today. (I am assuming 100 to be fast enough for anyone after dark.)

After the Melbourne-Sydney run I am even more a Ferrari fan and honestly consider the 330 GT to be the finest car I’ve driven. It is the first thoroughly practical Ferrari — suitable for every facet of motoring and the fastest and safest four-seater in the world.

MODERN MOTOR—August 1965