| 330 GT Registry |  |

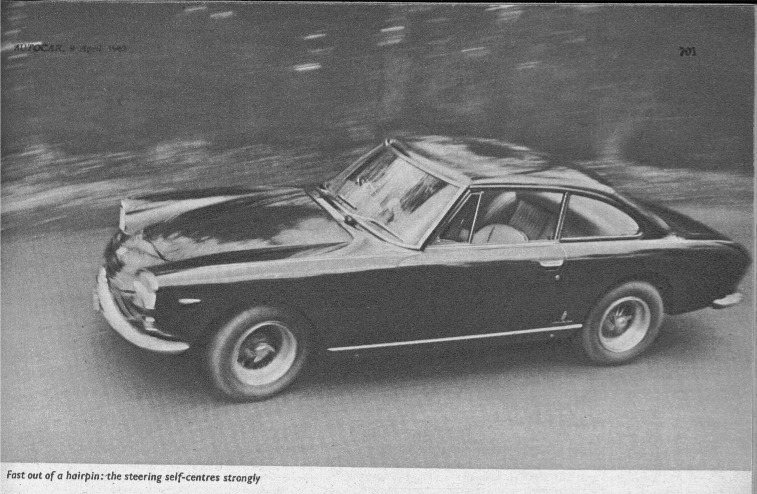

AUTOCAR , 9 April 1965

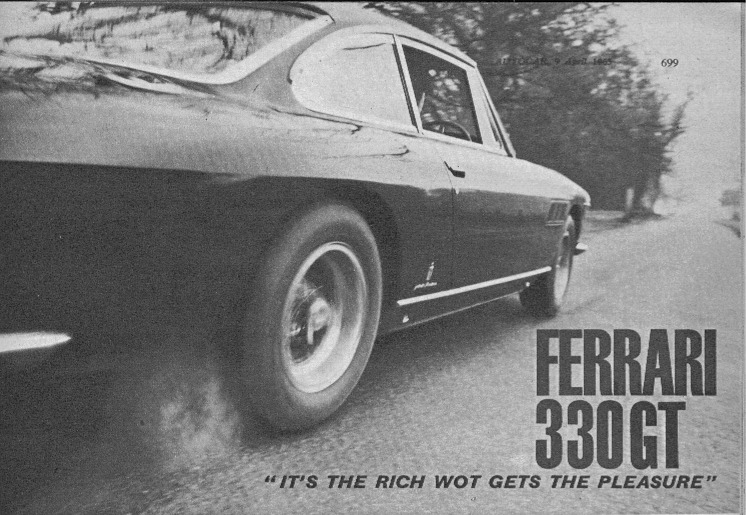

Some fast cars owe their performance to very large American engines, others to the work of tuning specialists, but the Ferraris offered for sale to ordinary people are in a third category. Built by a company which has been race-orientated for many years, they are to be regarded as competition cars “cooled off” a little for docility and comfort on the roads. The main advantage is that nothing mechanical is stretched or strained; on the contrary, there is plenty in hand. Thus the 330GT coupé which we have tried, though very fast indeed, is always comfortably within its performance potential, and its behaviour at speed is impeccable.

We have not included this car in our normal road test series because it is a private one and was lent to us by the Surrey owner (courageous, you may think), Terence Kane, whose pride and joy it is. This was done with the blessing of Colonel Hoare, the head of Maranello Concessionaires, but you do not take a chap’s 330GT and savage the clutch and transmission trying to pick up that elusive final tenth of a second on standing-start accelerations. We are expected to do that with manufacturers’ test cars, and those providing the fast ones often complain that we have not been brutal enough.

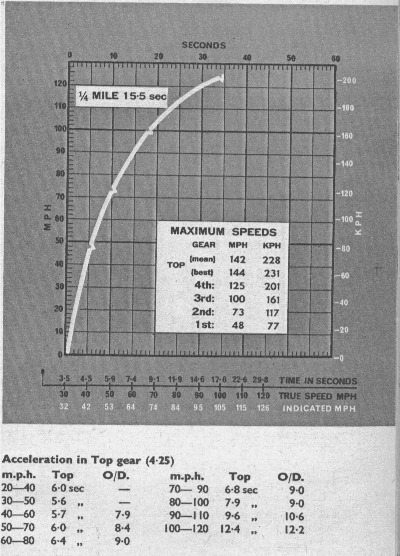

In the case of the Ferrari, we (Ronald Barker and self in this case), had a real go, but only three times in each direction on the MIRA timing straight instead of the usual three or four practice get-aways and then five or six timed runs each way for consistency and a good mean. So trim say (0.lsec off the standing-start figures of the 330GT for a fair comparison. We stuck carefully to the 6,600 r.p.m. recommended in the book and red-lined on the rev counter, and changed gear conventionally as quickly as we could—that is, without snatching the change and keeping the accelerator hard on the floor as some testers do. From the eager sweetness of the engine at 6,600 r.p.m. we guessed that it has quite a lot still in hand at this speed.

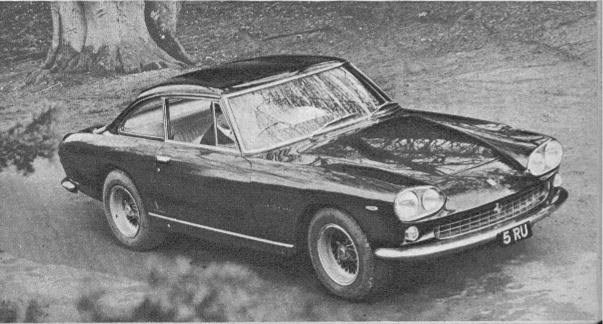

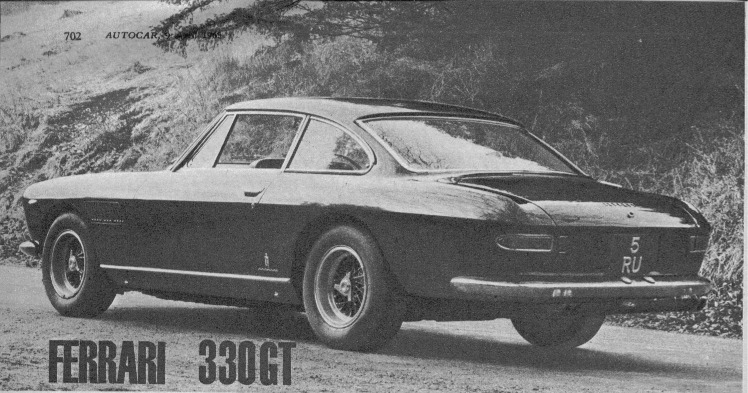

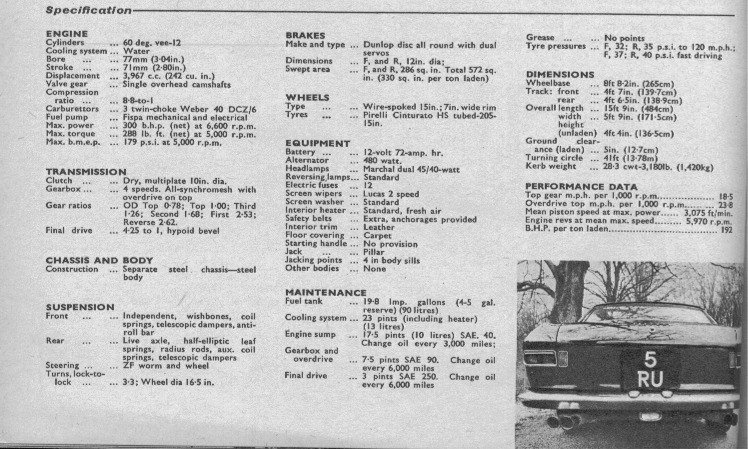

About the car itself; first this is a full four-seater with Pininfarina two-door coupé body. The boot is quite spacious and, the fuel tank holds practically 20 gallons. It is nearly 3in. longer than the S-type Jaguar but, as tested and carrying 5 gallons, it weighs 340lb less. With a full tank, its 30.5cwt is evenly distributed.

One of Pininfarina's most practical bodies.

|  |

PHOTOGRAPHS: MICHAEL COOPER |

As with all Ferraris, the number of the model refers to the capacity in cubic centimetres of one cylinder, so multiply 330 by 12 and you get 3,960 c.c. To be spot on you have to add another 7 c.c. in this case, so we can call it a 4-litre model. It is best only to glance at the total British price of this car (£6,522) bearing in mind that there is £1,172 purchase tax on it plus duty and delivery charges and, we hope, a fair commission for supplying such exotic things in small numbers. In its native Italy it costs the equivalent of £3,800 (lire 6.5 million). Even so a great deal is expected of such a marque and such a car. What in fact do you get?

As with all Ferraris, the number of the model refers to the capacity in cubic centimetres of one cylinder, so multiply 330 by 12 and you get 3,960 c.c. To be spot on you have to add another 7 c.c. in this case, so we can call it a 4-litre model. It is best only to glance at the total British price of this car (£6,522) bearing in mind that there is £1,172 purchase tax on it plus duty and delivery charges and, we hope, a fair commission for supplying such exotic things in small numbers. In its native Italy it costs the equivalent of £3,800 (lire 6.5 million). Even so a great deal is expected of such a marque and such a car. What in fact do you get?

Let’s take the satisfaction of ownership for granted. The Ferrari owner, anywhere, has arrived, and if one or two Latin Americans on the French Riviera, looking about 16 years old, do not altogether live up to their cars, who would blame the vehicle?

You have a very smooth and responsive vee-12 engine which in this car has been developed to pull evenly and accelerate away quite hard from 1,000 r.p.m. in top gear. (20-30 m.p.h. in 3.2sec).

In addition you have a very nice gearbox with overdrive, precise and quick to change and having synchromesh for the four ratios. The maximum speeds in each ratio are 48, 73, 100 and 125 m.p.h. as the book says. The speedometer is a touch fast and has a lazy needle; it settles at 106 m.p.h. when the car is truly doing 100, and you must change up from third.

Keeping to the top end of the performance, you find that the beefy acceleration is sustained up to 120 m.p.h. and continues on (overdrive) fifth between 110 and 130 m.p.h. The last 10 m.p.h. to a best speed of 144 m.p.h. (152 m.p.h. indicated) took perhaps a mile to build up and showed no sign of increasing after being held for at least another mile.

We were not quite able to repeat this speed in the opposite direction, and concluded that the normally usable maximum of this car is around 140 m.p.h.

The makers suggest that the overdrive (23.8 m.p.h. per 1,000 r.p.m.) normally should not be engaged below

60 m.p.h., yet the top gear (18.5 m.p.h. per 1,000 r.p.m.) feels like a third and the engine sounds to be running fast, so one instinctively looks for a higher ratio once clear of the 30 m.p.h. limits. Overdrive can be used only on top gear and a change down automatically cancels the selector.

At high speed the car really comes into its own—we decided that anything above 80 m.p.h. is better than below

it. The steering is excellent and scarcely a tremor can be felt through the wheel at any time. We drove with hands just on the wheel for many seconds at 120 m.p.h. and could not detect any movement in it at all. The car itself is exceptionally stable.

Handsome Borrani 15in. wheels carry huge 205mm (8.0in.) Pirelli tyres. For normal running, pressures of 32 p.s.i. front and 35 p.s.i. rear are recommended. For sustained speeds of over 120 m.p.h. Ferrari suggest 37 and 40 p.s.i. respectively. We felt that for road work this car may be over-tyred, with the result that at speeds below about 50 m.p.h. there is a certain deadness about the steering—as if it were brand new and still a bit stiff. (The car had done 6,000 miles.) The ride is also rather harsh unless the road is perfect; small ridges or coarse top dressing on the surface are felt and heard more than one would expect.

As already indicated, the tyres are very satisfactory indeed at high speeds and adhesion on dry roads is consistently good. On wet or greasy roads the car needs watching quite carefully if you want to use much of its power. A reminder about the rather unusual live-axle rear suspension: Flexible half-elliptic springs are used, polythene inserts separating their leaves. In addition, short coil springs surround the vertical telescopic dampers. The axle location is by two pairs of parallel radius arms and by the leaf springs. A slip-limiting device is incorporated in the final-drive differential.

On the steering pad at MIRA—a huge tarmac ring with concentric circles marked on it—we sampled the steering and cornering characteristics up to and beyond the dry adhesion limits before doing so on the track. Rather than under- or oversteering the car seems balanced in a corner. It is basically a slight understeerer when using gentle power round a bend. Pour on more power and you can bring the back end round progressively while holding a steady line by paying-off steering. Cut the power when cornering fast and, keeping the steering -wheel steady, the front wheels will stop slipping and cause the turn to tighten up. In any of these circumstances, normal corrective action immediately regains any loss of control. In wet or greasy conditions it is all too easy to use too much power and start the back end sliding.

On the steering pad at MIRA—a huge tarmac ring with concentric circles marked on it—we sampled the steering and cornering characteristics up to and beyond the dry adhesion limits before doing so on the track. Rather than under- or oversteering the car seems balanced in a corner. It is basically a slight understeerer when using gentle power round a bend. Pour on more power and you can bring the back end round progressively while holding a steady line by paying-off steering. Cut the power when cornering fast and, keeping the steering -wheel steady, the front wheels will stop slipping and cause the turn to tighten up. In any of these circumstances, normal corrective action immediately regains any loss of control. In wet or greasy conditions it is all too easy to use too much power and start the back end sliding.

With the introduction of the 330GT came a revised Dunlop disc brake system. Separate hydraulic circuits are provided, with twin servos giving independent operation, front and rear. The brakes, which require only moderate pedal loads, are very reassuring at all speeds and the tendency with very fast cars to fit hard pads for high-speed braking which give insufficient bite at low speeds has been avoided.

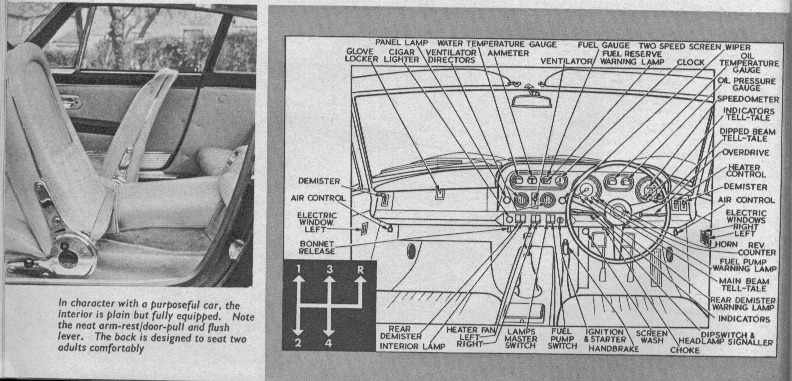

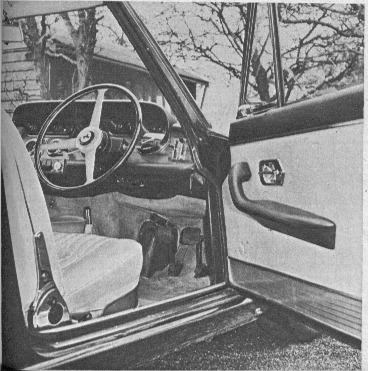

The interior is very well equipped and finished in quiet good taste. An elaborate heating system and separate adjust.. able fresh-air ducts in the middle of the instrument panel, plus extractor rear windows, provide a variety of hot and cold air flows, the control of which we did not completely master. The rear window de-misting fan does its job energetically, but produces an unwelcome reflection in the rear window.

A long reach is needed to depress the accelerator fully to what one could aptly call a flat-out position. This calls for an uncomfortable toe-pointed attitude, a deterrent perhaps to prolonged full-throttle driving. The pedal is set below the level of that of the brake, and this leads to an unnecessarily long lift of the foot from “go” to “stop.” Sound-damping felt and carpet have reduced the clearance above the clutch pedal so that the toe of a size nine shoe does not clear. If the driver’s quarter-light is opened more than a crack its corner catches against the run of the steering wheel.

A long reach is needed to depress the accelerator fully to what one could aptly call a flat-out position. This calls for an uncomfortable toe-pointed attitude, a deterrent perhaps to prolonged full-throttle driving. The pedal is set below the level of that of the brake, and this leads to an unnecessarily long lift of the foot from “go” to “stop.” Sound-damping felt and carpet have reduced the clearance above the clutch pedal so that the toe of a size nine shoe does not clear. If the driver’s quarter-light is opened more than a crack its corner catches against the run of the steering wheel.

A pleasing wide binnacle in front of the driver carries instruments which have plastic “glasses”—for safety we presume; at night they have a dusty look and feeble illumination. We very much admired the neat armrests on the doors. Rounded and leather-covered, they sweep up at the front to form a handle to grab or to pull the door shut, and just above is a flush trigger for the door latch. Silent electric window motors give fine control to “inch” the glasses up or down.

To appreciate this car to the full one should live with it for months, not days. We have noted that Ferrari owners usually make modifications to equipment and controls to suit themselves, and so any small personal likes and dislikes we have for details in someone else’s car are unimportant.

After our brief outings and some 450 miles of driving, we returned this taut and exciting car with great regret and a certainty that it would have become even more satisfying as time and miles passed in its company. M.A.S.

Copyright 1965 Iliffe Transport Publications Ltd.

Published with permission from Autocar